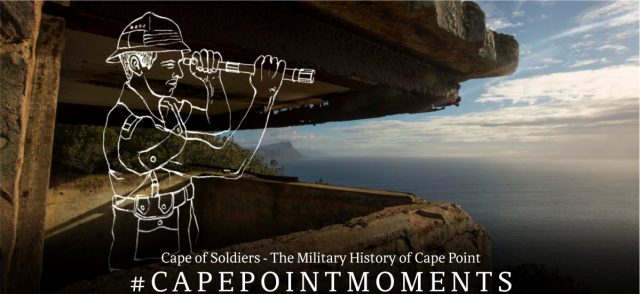

Cape of Soldiers: Point of interest

The year 1939 was the end of a long and difficult war over the soul of Cape Point, and the start of a long and difficult war over the soul of Europe.

On one side of the dispute at Cape Point was a Johannesburg-based property developer who wanted to buy the largest farm in the area and turn it into a luxury resort. They were opposed by a group of concerned environmentalists and Cape Point residents, who wanted the government to buy the land and declare it a national reserve.

The good guys won. In 1939, the Cape Divisional Council did buy the land with the intention of declaring it a reserve. But in the same year Hitler invaded Poland, sparking the start of World War II.

So in the end the land did not fall into the hands of the greedy property developers; but it did not immediately go to the environmentalists either.

In 1939 Cape Point fell into the hands of the South African military.

The strategic importance of Cape Point is fairly obvious. Before the Suez Canal was built (in 1869), any ship taking the shortest distance between the West and the East would need to pass this tip of the African continent.

But even after the Suez Canal was built, the importance of Cape Point did not diminish. The canal was a vulnerable and limited maritime passage to the East.

Especially in times of war.

Early history – Manhandling cannons

Cape Point’s earliest use by the Dutch East India Company was as a signal point. Ships sailing into Table Bay from the East were heralded by the firing of a series of canons. The first of these was at a lookout point on Kanonkop, so named because an old Dutch canon was discovered there in the years preceding the second World War.

One of the more remarkable signalmen in Cape Point, stationed somewhere on the west coast of the reserve in the 1800s, was said to inhabit his humble lookout in the company of his fertile wife and their nine children. “This must have been the job in the Cape with the best views but the most boring remit,” mused Cape Point documentarian, Michael Fraser. “No wonder he had so many children.”

During the First World War, the Cape Mounted Rifles were stationed at Cape Point, primarily to guard the newly-built second lighthouse. In the years between the World Wars, the promontory was used as a training facility by temporary camps that were erected along the banks of the Klaasjagers River, which marks the northern boundary of the Reserve.

An old photograph captioned “Manhandling a field-gun through the fynbos. SA Permanent Garrison Artillery, Cape of Good Hope, 1928” shows two rows of 15 men dressed in smart, pale uniforms and wearing stiff-peaked army hats.

They are dragging an enormous, polished canon over the sandstone and scrub of the Reserve. Each row of men is pulling a rope attached to the wheel of the cannon. It is backbreaking work. Needless to say, the men are not smiling for the camera.

WWII – Code Name: Blue Gums

“Fortunately,” writes Commander W.M. Bisset of the South African Navy, the second World War proved to be “a great anti-climax because South Africa was spared an attack on her coastal cities and towns by enemy warships and aircraft.”

After much of the newly-proclaimed Cape Point Reserve was cordoned off from the public for exclusive military use, six FOPs (forward observation posts) were built on the promontory.

Their codenames were:

- Cobra (at Slangkop)

- Bosch (at Olifantsbosch)

- Vasco (at Cape Point)

- Diaz (overlooking the False Bay on the Point)

- Crow (at Scala)

- Blue Gums (between Miller’s Point and Smitswinkel Bay).

These were all built and operational by 1942.

The radar stations built into clandestine nooks of the Cape Point cliff face were operated by the Special Signal Services the 61st Coastal Defence Corps – said to be composed almost entirely of women. Their exact location was top secret. Had their existence and location been discovered, enemy bombers would have made sure that the promontory would not have been the same size and shape as it is today.

There are also unconfirmed anecdotes about one man who would join the fishermen in False Bay with a rod and tackle that had been rigged to create an antenna with which he would signal coded messages of military activity to enemy ships.

Decades later, people buying houses in Kalk Bay and Fishoek would find military equipment in dusty cellars that were attributed to spying activity. (There were enough Nazi sympathisers in South Africa at the time to lend these tales some credence – there was a strong public lobby at the time for South Africa to join the war on the side of the Germans!)

In 1947, two SA air force pilots wrote a letter to the War Stores Disposal Board in Pretoria to ask if they could access the Blue Gums FOP. The “small concrete blockhouse, woodshed, water tank and a latrine adjoining it” were overgrown with fynbos and forlorn after several years of neglect.

Nonetheless, the fixer upper had great views, and the pilots promised to give it some carpentry and attention if the army allowed them to use it as a weekend fishing retreat.

Three months later the pilots received a response: no.

But it was certainly worth a try.

For more on the Cape of Soldiers, visit Cape Point now.